What is the Wayback Machine?

The Wayback Machine (often stylized simply “Wayback Machine”) is a free online archive and service run by the Internet Archive (IA), a nonprofit dedicated to preserving digital content. It allows users to view and browse archived versions of web pages — from decades ago to recent past — giving us a glimpse of how the internet used to look.

In essence, the Wayback Machine acts like a time-capsule for the web. By entering the URL of any publicly accessible website, you can access snapshots saved over time and see what that page looked like on different dates.

Origins and History

The roots of the Wayback Machine go back to the 1990s. The Internet Archive was founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle and Bruce Gilliat with the ambitious mission of providing “universal access to all knowledge.”

Between 1996 and 2001, the IA was quietly archiving web pages — storing them on digital tape. By 2001, the archive had grown massive, and the Wayback Machine was publicly launched. At launch, it already contained more than 10 billion archived pages.

The name “Wayback Machine” is inspired by the fictional time-traveling device from the 1960s animated show The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show — specifically the “Wayback Machine” used by characters to travel back in time and witness historical events.

Over time, the archive has grown dramatically. As of recent years, the Wayback Machine holds hundreds of billions — by some counts over 900 billion — web pages, making it the largest publicly accessible web archive in existence.

How It Works — Under the Hood

Web Crawling & Snapshots

To build its archive, the Wayback Machine relies on automated programs called web crawlers (also known as “spiders”). These bots periodically scan the public web, visiting millions of domains, and capturing the publicly available content — including HTML, images, CSS, and other assets.

Each time a crawler visits a site, the content is stored and timestamped, creating a “snapshot.” Over time, for each URL, the archive builds a chronological record of changes. Snapshots are indexed by URL and date, so users can later retrieve a particular version.

User Interface & Access

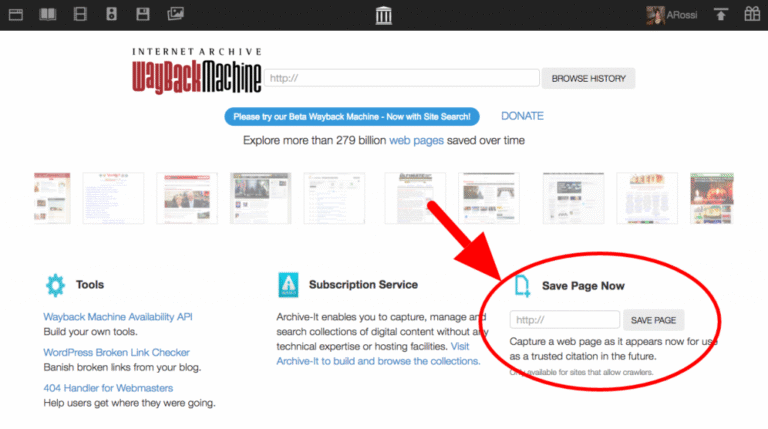

When you visit the Wayback Machine website, you can enter a full URL in the search box. If that page has been archived, you are presented with a timeline and a calendar view — dots on the calendar mark dates when snapshots were taken. Clicking a date will load the version of the page as it existed on that day.

There is also a “Save Page Now” feature. This allows users to manually archive a page — useful if you want to guarantee that a particular page gets preserved at that moment (for instance before it gets changed or removed).

For developers, the Wayback Machine offers APIs — such as the “Wayback Availability JSON,” the “Memento” protocol, and the “Wayback CDX Server” — to automate querying of saved URLs, checking if a page is archived, or retrieving metadata of snapshots.

Why It Matters — Use Cases and Significance

The Wayback Machine is more than a curiosity — it has become a critical tool with real impact. Here are several of its key functions and why they matter.

- Historical & Cultural Preservation: The web evolves fast. Websites get redesigned, content is deleted, domains expire. The Wayback Machine preserves snapshots of sites — from early 2000s homepages to long-defunct personal blogs — offering a historical record of our digital past. This is invaluable for researchers, historians, or anyone curious about how the web (and society’s use of it) has changed.

- Lost Content Recovery: If a page has been deleted, moved, or altered drastically, the Wayback Machine can often recover what once existed — whether it’s a defunct news article, an old blog post, or a webpage that simply vanished. This makes it useful for retrieving lost information, verifying sources, and understanding website histories.

- Journalism & Fact-Checking: Journalists may need to reference sources as they existed at a certain moment. The Wayback Machine lets them view what public content looked like at that time — even if the site has since changed, or content deleted.

- Web Development & SEO: Developers or web‐masters can use the archive to track changes over time, debug issues by seeing when a page broke or changed behavior, and restore previous versions if needed. SEO professionals sometimes check older versions of pages to understand what content performed well before redesigns.

- Legal & Investigative Research: Archived web content can serve as evidence — for example, to show what claims a website made at a certain date, or to recover documents no longer publicly available. The time-stamped snapshots act as a kind of public record.

- Academic & Social Research: Scholars studying the evolution of the web — how design trends, content types, or user behavior changed — rely on the Wayback Machine as a large-scale archive. Some research even uses archived data to analyze long-term shifts in media consumption, web architecture, or online culture.

Limitations & What the Wayback Machine Doesn’t Capture

Despite its breadth and power, the Wayback Machine is not a perfect mirror of the entire internet. There are several important limitations that users should be aware of:

- Not Every Page Is Archived: The archive only stores publicly accessible content that its crawlers can reach. Websites that block crawlers (e.g. via a

robots.txtpolicy) may be skipped or excluded. Also, pages behind logins, paywalls, or other dynamic content often aren’t captured. - Incomplete Archiving of Complex Sites: Modern websites often rely on dynamic content: JavaScript, interactive features, database-driven navigation, embedded media, etc. The Wayback Machine does best with static HTML content; complex interactive or dynamically generated parts may fail to archive or render properly.

- Inconsistent Snapshot Frequency: Even for archived sites, crawlers may capture them only occasionally — months or even years may pass between snapshots. That means many edits or versions might be lost.

- Respect for Robots.txt & Site Owner Requests: The Internet Archive respects site owners’ wishes. If a site requests not to be archived, or uses robots instructions to block crawling, the Wayback Machine may omit or later remove archived content.

- Not a Mirror of Live Interactivity: While archived pages reproduce layout, text, images, and links, interactive features — such as search within the archived site, browsing dynamic comment threads, or real-time data feeds — often don’t work as in the original. Archived pages are generally static snapshots.

Because of these limitations, the Wayback Machine should be viewed as a powerful, but imperfect, digital archive — a remarkably broad and rich resource, but not a foolproof guarantee that everything once on the web will be recoverable.

The Broader Significance: Why Web Archiving Matters

In an age where much of our cultural, journalistic, and social history lives online, the impermanence of websites poses a serious risk. Domains expire, websites are redesigned or shut down, and valuable content — articles, blogs, forums, public statements — can disappear. Without tools like the Wayback Machine, these digital artifacts might vanish forever.

The Wayback Machine thus serves as a collective memory bank for the web — a publicly accessible, time-stamped archive that helps ensure that at least some record is preserved. For historians, journalists, researchers, litigators, or just curious individuals, it offers a way to “turn back time” on the internet and revisit its past.

Moreover, as the web continues to evolve — with more multimedia, dynamic content, social platforms, databases — the role of archives becomes even more crucial. What might seem like minor blog posts or forgotten pages today could become important social or historical documents decades from now.

At the same time, the limitations of archiving — due to dynamic content, crawler restrictions, or site owners’ opt-outs — highlight the fragility of digital history. Not everything can be secured, and some information may still be lost.

Recent Developments & Current State

The archive continues to grow. As of recent counts, the Wayback Machine has preserved hundreds of billions — or even approaching one trillion — web pages. This underlines both the enormous scale of the internet and the ambition of digital preservation efforts.

Organizations, researchers, and everyday users continue to rely on it — for investigating web changes, recovering lost content, documenting online culture, or preserving digital heritage. Its APIs and manual “Save Page Now” tool provide flexibility, enabling both automated archival at scale and ad-hoc preservation of critical pages.

At the same time, the challenges remain. As websites grow more complex, with dynamic content and interactive elements, archiving becomes harder. And because archiving depends on access and crawling permissions, some content may escape preservation entirely.

Conclusion: The Importance of the Wayback Machine

The Wayback Machine stands as one of the most important digital preservation tools ever built. It offers a unique capability — time travel on the web — letting us see what sites used to look like, recover lost pages, or trace the evolution of online content over decades. For researchers, journalists, developers, historians, or curious netizens, it’s an invaluable resource.

Yet it also underscores a sobering truth: the web is fragile. Without concerted and ongoing efforts, much digital culture could be lost forever. The Wayback Machine isn’t perfect — it doesn’t capture everything — but it represents a collective attempt to safeguard our shared digital memory.

As the internet continues changing at breakneck speed, tools like the Wayback Machine — and the institutions behind them — play a critical role in preserving history, knowledge, and the collective memory of our digital age.